The Haunting History of Noel Coward's Blithe Spirit

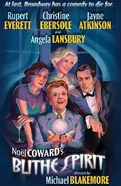

In the spring of 1941, as Londoners endured the Blitz, superstar playwright Noel Coward slipped away to Wales to work on a new script. “Title [is] Blithe Spirit,” he wrote in his diary. “Very gay, superficial comedy about a ghost. Feel it may be good.” Six days later, the play was finished—and now, almost seven decades later, this enduringly popular comedy is being revived on Broadway with a cast headed by Rupert Everett, Angela Lansbury and Christine Ebersole. Here’s a look back at the life and career of a playwright whose wit remains timeless.

The First Noel

With a name inspired by the proximity of his birthday to Christmas December 16, 1899, Noel Peirce Coward was indeed a happy holiday gift to his parents, who had lost their first son to spinal meningitis the previous year. The family had little money; Noel’s father was an unsuccessful piano tuner and salesman, and his Momma Rose-ish stage mother pushed her precocious little boy into a professional stage debut at age 10. Answering an ad for “a star cast of wonder children,” he won a role in a play called The Goldfish by tap-dancing “violently” while his mother played “Nearer My God to Thee” on the piano. Also hired that day: young Gertrude Lawrence, who grew up to become Coward’s frequent co-star and muse.

Great success came quickly. As his literary executor Sheridan Morley summed it up in the memoir Coward, “By 15, he had acted with the sisters Lillian and Dorothy Gish in D.W. Griffith’s silent film Hearts of the World. At 20, he was a produced playwright, and by the time he was 30 he had written the drug play The Vortex, the epic 400-cast Cavalcade, the everlasting Private Lives and the lyrical operetta Bitter Sweet.” In all, Coward penned 60 produced plays and more than 300 songs, plus memoirs, diaries, short stories and screenplays.

In addition to a workaholism driven by his desire to escape poverty, Coward built his glittering career by writing parts perfectly suited to one particular leading man: himself. “In his clipped, bright, confident style, Coward irresistibly combined reserve and high camp,” critic John Lahr noted in Coward the Playwright. “Coward was his own hero and the parts he created for himself were, in general, slices of his legendary life.” These included successful writers Charles in Blithe Spirit; Leo in Design for Living, men of the theater Garry in Present Laughter and world-traveling bon vivants Elyot in Private Lives.

Clad in silk dressing gowns, hair perfectly slicked back, cigarette holder and martini in hand, Coward and his onstage alter egos oozed sophistication. Coming of age in the 1920s, he had no qualms about celebrating frivolity for its own sake. As a closeted gay man, he treated sex and romance lightly, even rebelliously. His characters—both men and women—seemed to possess no internal filter, saying exactly what they were thinking to great comic effect. “I’m glad I’m normal,” Amanda’s young second husband, Victor, announces at one point in Private Lives. “What an odd thing to be glad about,” she replies, adding later, “I think very few people are completely normal really, deep down in their private lives.”

A Tale of Two Wives

By the beginning of World War II, Noel Coward was hugely famous on both sides of the Atlantic. He adored the creative energy of New York, where he starred in Broadway productions of Design for Living opposite Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne and Private Lives opposite Gertrude Lawrence, Coward’s lifelong crush Laurence Olivier and Olivier’s then-wife, Jill Esmond. He traveled the world to drum up support for Britain’s war effort, but an ever-present need for money spurred him write a new comedy about a man haunted by the ghost of his first wife.

Blithe Spirit “fell into my mind and on to the manuscript,” Coward later wrote of writing the play in less than a week. In a production schedule that seems unbelievably fast by today’s standards, the play opened at London’s Piccadilly Theatre just six weeks later, on July 2, 1941, and premiered on Broadway at the now-demolished Morosco Theatre on November 5, 1941. Even more amazing is the fact that only two lines were dropped and none were altered during rehearsal of what the playwright dubbed “An Improbable Farce in Three Acts.”

As Blithe Spirit begins, novelist Charles Condomine is preparing to host a seance to be conducted by a medium known as Madame Arcati. For him, it’s a jokey way to do research for a new novel, appropriately titled The Unseen. Unexpectedly, however, the evening ends with the spectral reappearance of his first wife, Elvira pronounced Elveera, who has been dead for five years. Only Charles can see her, which causes immediate problems with his very-much-alive second wife, briskly efficient Ruth. Charmed at first by the ghostly Elvira—with whom he shared a more passionate union than with Ruth—Charles quickly gets caught between the two.

“I remember her physical attractiveness, which was tremendous, and her spiritual integrity, which was nil,” Charles says of Elvira. As for wife #2, when Ruth ponders aloud whether Charles would remarry if she passed away, he says airily, “You won’t die—you’re not the dying sort.”

Coward correctly surmised that a comedy about death would resonate among audiences who were, in real life, carrying on in a city under daily threat of attack. Although novelist Graham Greene called Blithe Spirit “a weary exhibition of bad taste,” the public loved it, and the play went on to a record-setting London run of 1,997 performances. Without spoiling the well-plotted ending, suffice it to say that the forces of death are tamed in Blithe Spirit in a way that warmed the hearts of wartime theatergoers.

Haunted House

Blithe Spirit’s visually inventive style made it perfect for the big screen, and Coward’s frenemy Rex Harrison who thought the playwright was a lousy actor played Charles in David Lean’s 1945 movie opposite original London stage stars Kay Hammond as Elvira and Margaret Rutherford as Madame Arcati. Coward himself played Charles in an Emmy-nominated 1956 TV version with Lauren Bacall ! as Elvira, Claudette Colbert as Ruth and future Happy Days star Marion Ross in the small but pivotal role of the Condomines’ maid.

More than 40 years passed before Blithe Spirit got its first Broadway revival, but Charles & Co. made it back to the Great White Way in musical form in 1964. High Spirits, starring Tammy Grimes as Elvira and Beatrice Lillie as Madame Arcati, ran for 375 performances and earned eight Tony nominations, including one for Coward’s direction. The chorus included “Ronnie Walken,” who went on to movie fame as Christopher Walken. A 1987 revival of Blithe Spirit ran for three months and starred Richard Chamberlain as Charles, Blythe Danner as Elvira, Judith Ivey as Ruth and Geraldine Page in a Tony-nominated performance as Madame Arcati. Tragically, Page died of a heart attack at age 62 two weeks before the end of the run.

Now Coward’s “psychic ménage-a-trois,” as John Lahr calls Blithe Spirit, is back on Broadway with Michael Blakemore as director. A double Tony winner in 2000 for the unusual combo of Kiss Me, Kate and Copenhagen, Blakemore made his name on Broadway in the early 80s with the farcical Noises Off. “I’d seen Blithe Spirit as a kid in Australia, and I’d sort of forgotten how well constructed it is, with a lot of surprises along the way,” the 80-year-old director says. “It’s a brilliant contrivance that puts the characters in situations that are appalling for them but hilarious for us."

Two seasons ago, Blakemore coaxed four-time Tony Award winner Angela Lansbury back to the stage as a retired tennis champ in Deuce, and he’s done it again with Blithe Spirit’s Madame Arcati. “Angela smells good material when it comes under her nose,” he says, “and she was born to play this part. It’s both funny and touching, and I think she’ll be amazing.”

Caught between Christine Ebersole as Elvira and Jayne Atkinson as Ruth is British actor Rupert Everett, whose ability to deliver a bon mot has served him well in works by Coward in a London revival of The Vortex and Oscar Wilde The Importance of Being Earnest on both stage and screen. “I think Rupert will bring a certain quirkiness Charles that will be both true to the period but also true to ours,” Blakemore says of Everett’s Broadway debut. “We’re setting the play in 1938, but it can also have a slightly more modern slant.”

A Talent to Amuse

In the last three decades of his life, Noel Coward achieved acclaim as a cabaret performer wowing ’em in Vegas, no less, in addition to acting in and directing his own plays. His final London stage appearance was in his own Suite in Three Keys in 1966, and he was knighted in 1970. As his health declined, he retreated to Jamaica, where he entertained friends and painted landscapes. He died there on March 26, 1973, and was buried on the island.

Though some of his contemporaries questioned whether Coward’s plays would endure apart from his own stylish persona, his best comedies feel vivid and fresh. Coward himself would have been amused by the current tabloid culture and fixation with celebrities; after all, he managed to market himself for half a century with a fascinating mix of vanity and self-deprecation. Asked by an interviewer how he expected to be remembered, he responded with one of his most-used words: “By my charm.”